Non-disclosure and misrepresentation in the Health declaration for Life and Health insurancePersonal

Ana Luisa Villanueva

Chief Medical Officer Life, Health & Accidents MAPFRE RE

Madrid - Spain

The insurance contract is a private agreement between two parties, the insurance company and the insured, which represents for the insurer the legal obligation to cover the consequences of an uncertain event, or claim, and for the insured the payment of a premium to compensate this warrant.

A law, the Insurance Contract Act, very similar in scope and legal technique in all European Union countries, governs these contracts.

In Spain, the topic we are discussing is present in the LCS (Insurance Contract Act), article 10.

Article 10 addresses the obligation of the insurer to submit a questionnaire to the policyholder, who is required to answer the questions truthfully. If the questionnaire does not have the necessary questions to know the health state of the applicant, the latter is exonerated of the obligation.

If the insurer finds out that the policyholder has not given truthful answers to questions asked in the questionnaire, there is a period of a month to inform the insured and avoid the policy.

This fraudulent or misleading attitude usually refers to the failure to reveal a relevant fact when applying for an insurance contract

If claim takes place before the insurer notifies any irregularity to the insured, the insurer can cover the benefit applying proportionality between the agreed premium and the premium that should have been paid. However if there is fraud form the insured side, that is, clear intention to mislead on his or her health state, the insurers is entitled to avoid the policy.

Three main conclusions up to now:

- The importance of a clear and direct questionnaire to avoid non-disclosure.

- The need of a sharp risk management process to avoid declining benefits due to incomplete questionnaires.

- To understand, know and identify fraud or non-disclosure.

If we look for the definition of “Dolo” (Latin word for malice, wilful misconduct or fraud, commonly known in English as nondisclosure or misrepresentation) in the insurance dictionary we find the following definitions:

- Dolo: Fraudulent or misleading attitude from one party to the insurance contract with the intention of causing harm the other contracting party.

- Artifice or simulation used by someone to act deliberately against another one. It is a synonymous with bad faith.

This situation of fraud, within the insurance contract, can affect both the insured (nondisclosure or claims) and the insurer (terms of the contract).

This fraudulent or misleading attitude usually refers to the failure to reveal a relevant fact when applying for an insurance contract, which is also an essential condition for the contract to be legally binding.

The insurance contract is a contract of utmost “good faith”, which means that both parties are under a strict duty to deal fully and frankly with each other. Thus, applicants must disclose all facts that are material (or relevant) to the risk for which we seek cover.

A material (relevant) fact is one that would influence underwriting when deciding whether to accept the risk and the terms and conditions that should apply. If the applicant fails to disclose or misrepresents a material fact and this induces the insurer to accept the proposed risk, the legal remedy is to avoid the policy.

Following the approach of the British “Financial Ombudsman Service” and taking into account both the law and good industry practice, the disputes concerning non-disclosure and misrepresentation can be caused by three situations:

- The way the insurer asks the question about the risks that need to be known.

- The way an answer can induce (or influence) the acceptance of a risk. If the answer had been made in a different way, the risk would have not been accepted or accepted under different terms.

- Only if the two above situations take place, then we can consider whether the applicant’s misrepresentation was an honest mistake, a dishonest attempt to mislead or it was due to some degree of negligence.

The FSA (Financial Services Authority) is the regulator body for the financial services industry in the UK. Since January 2005, it also regulates insurance activities. It is an independent non-governmental body, given statutory powers by the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. They are accountable to Treasury Ministers and through them, Parliament. This public body published the Insurance Code of Business (ICOB) on 14 January 2005 to safeguard the good industry practice. They count on an official independent expert in settling complaints called the FOS (Financial Ombudsman Service).

Clear questions

The insurer must provide evidence that it asks the applicant clear questions. There are different ways to ask these questions:

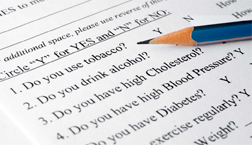

In a traditional paper questionnaire. The applicant has to write down the answers to a series of questions. If the answer is positive, he or she should provide an accurate definition as well as date of diagnosis. This format has the disadvantage of space limitation. We cannot name all disease or ask everything we would like. Sometimes the length of the question or the terms used in the wording may lead to non-disclosure or misinterpretation.

Health questionnaires can be in three formats: physical or in paper, phone call and digital via internet

In a tele-interview or telephone questionnaire, recorded by the computer system. Depending on the insurer, the recorded call can be transcribed, printed and sent to insurer for signature.

This questionnaire has precise questions that open into new ones according to the answer provided, making misinterpretation very difficult. In most cases, this process allows the direct identification of the impairment/ disorder or condition that may generate a request for a medical report.

Online questionnaire, through internet. This format is similar to the one used in tele-interviews. The process has security systems not to let the applicant change or experiment with the answers. There is no space limitation as in the previous format. Time is the main constrain. Questions are easy and specific for the applicant to decide quickly on the purchase of insurance.

Inducement

Legally, the insurer must establish that the non-disclosure or misrepresentation may lead to avoid the policy. In the UK, questionnaires commonly include a paragraph, at the very beginning, warning the applicant of the possibility of avoiding the contract in case of non-disclosure or misrepresentation.

The way the applicant provides the answer induces the acceptance of a risk that should not be accepted. For example, the preventive use of certain drugs may hide other impairments, not disclosed somewhere else.

This is difficult for the insurer, as the underwriter should request the applicant for further information to evidence the provided answer.

The applicant’s state of mind

The insurance industry should improve the way to obtain relevant information

We must note that not all instances of nondisclosure or misrepresentation breach the duty of utmost good faith.

The FOS (Financial Ombudsman Service) has identified four types of non-disclosure: deliberate, reckless, innocent and inadvertent.

It is possible to deliberately non-disclose without being fraudulent. While dishonesty is one of the essential criteria for fraud as mentioned earlier, there must also be deception, designed to obtain something to which you are not entitled to be considered a fraud. For example, insureds might deliberately withhold information they are embarrassed about. Although, by doing so, they are acting dishonestly and deliberately, they are not acting fraudulently because there is no deceitful intention to obtain an advantage. An example of this situation could be the non-disclosure of the real alcohol, tobacco or substances consumption.

Deliberate non-disclosure

Deliberate non-disclosure. The applicant deliberately provides information they know to be untrue or incomplete

Applicants deliberately mislead the insurer if they dishonestly provide information they know to be untrue or incomplete. If the dishonesty is intended to deceive the insurer into giving them an advantage to which they are not entitled, then this is also a fraud and, strictly speaking, the premium does not have to be returned. An example of this situation is the non-disclosure of a well-known impairment, such as diabetes type I, which requires a daily shot of insulin for treatment.

Reckless non-disclosure

Reckless non-disclosure: Applicants recklessly give answers without caring whether those answers are true or false

Applicants breach their duty of good faith if they mislead the insurer by recklessly giving answers without caring whether those answers are true or false. An example might be when the applicant signs a blank health questionnaire and leaves it to be filled out by someone else. The applicant has signed a health declaration that “the above answers are true to best knowledge and belief”, but does not know what those answers will be.

Innocent non-disclosure

Innocent non-disclosure: The non-disclosed information is not considered as relevant material

Applicants act in good faith if their nondisclosure is made innocently. This may happen when the question is unclear or ambiguous, or because the relevant information is not something that they should know. In these cases, the insurer will not be able to avoid the contract and, subject to the policy terms and conditions, should pay the claim in full. We find an example in the non-disclosure of hepatitis when the infection took place in adolescence and there were no symptoms since then, so the applicant has forgotten all about it.

Inadvertent non-disclosure

Inadvertent non-disclosure: Unintentional mislead of information

The applicant may also have acted in good faith if the non-disclosures are made inadvertently. These are the most difficult cases to determine and involve distinguishing between today behaviour that is merely careless and that which amounts to recklessness. Both are forms of negligence.

Inadvertence occurs when the customer unintentionally misleads the insurer. This can frequently occur by failing to read the questions and check the answers. When this happens, there is no breach of duty of utmost good faith. The non-disclosure of a hearing impairment caused by an infection and treated with hearing aid is a good example.

Legislation in countries such as Spain, France and United Kingdom LCS, art 10, Code d’Assurances, L-113-3 and 9 and Consumer Insurance (Disclosure and Representations) Act 2012, Schedule 1, section 4(3), part 1, express the duty of the applicant to disclose all material facts and provide true and complete information.

In any of the above situations, the resolution of a claim may fall into any of the following:

- Decline the claim since if material risk had been disclosed, the policy would have not been accepted, which could also involve returning the premiums paid.

- Avoid the policy: decline the claim and cancel the policy.

- Pay the claim applying a proportionate remedy according to the underwriting if complete information were available.

- Pay the claim if non-disclosure was not relevant for underwriting.

Despite the clear distinction of the different situations that may take place at time of disclosure, the difficult technical argument grants the courts discretion to determine non-disclosure from the insured side.

| Non-Disclosure | Description | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Inadvertent Innocent |

|

Pay the claim in full. |

| Reckless |

|

Apply a proportionate remedy. |

| Deliberate or without any care |

|

Avoid the policy. Decline the claim and cancel the policy from inception. |

Conclusion

We still have a long way to go to draw a clear line between fraudulent and inadvertent nondisclosure. Therefore, the insurance industry should improve the way to obtain relevant information through:

- Questionnaires with good, clear and defined questions.

- Aware the applicant of the relevant information to provide. This implies not taking for granted that they understand the meaning of severe condition or impairment, know the complications from their disease and recognize an incurable disease.

- Provide explanations on limiting / delimiting clauses.

- Clear management process to improve performance of participants and direct transmission of the information for risk assessment.

Bibliography

Ley del Contrato de Seguros. Ley 50/1980 de 8 de octubre.

Insurance terms Glosary:

www.santander.com

www.mapfre.com/fundacion/es/centrodocs/diccionario-mapfre-seguros.shtml

www.axa.es

Insurance Contract Law, A Joint Scoping Paper. The Law Commission and The Scottish Law Commission, UK 2006.

Le Code des assurances, Version consolidée au 7 juillet 2012.

Non-disclosure in insurance cases. “Ombudsman News” issue 46 May/June 2005.

The Insurance Code of Business ICOB; FSA Handbook 05/08/2008.

Customer Insurance (Disclosure and Representation) Act 2012 UK government.

ABI Code of Practice. Managing claims for Individual and Group Life, Critical Illness and Income Protection Products. January 2009.

Biomedicina y derecho sanitario, tomo VII Universidad Europea de Madrid, 2010 ISBN: 978- 84-937689-2-8.

Declaración del riesgo y enfermedades anteriores a la contratación de un seguro Comentario a la STS, 1ª, de 31.12.2003, a partir de la nueva jurisprudencia del año 2004. Begoña Arquillo Colet, Bufet Castelltort Barcelona.