The U.S. Federal Crop Insurance Program in 2012 and BeyondAgricultural

Benjamin S. Wilner

Director - Economic Advisory Services.

Grant Thornton LLP.

Chicago, Illinois - U.S.A.

Frank Schnapp

Senior Vice President.

National Crop Insurance Services (NCIS), Inc.

Overland Park, Kansas - U.S.A.

A Brief History of Crop Insurance in the United States

Insurance protection against damage to growing crops has been available to farmers in the United States since the late 1800’s. Crop- Hail insurance provides protection against damages caused by hail, fire, and lightning, as well as transit of harvested crops to storage. Additional perils such as wind are insured on an optional basis. Private sector insurers at one time had offered multiple peril crop insurance, but the effort floundered due to the difficulty in setting adequate rates to cover losses resulting from widespread crop disasters.

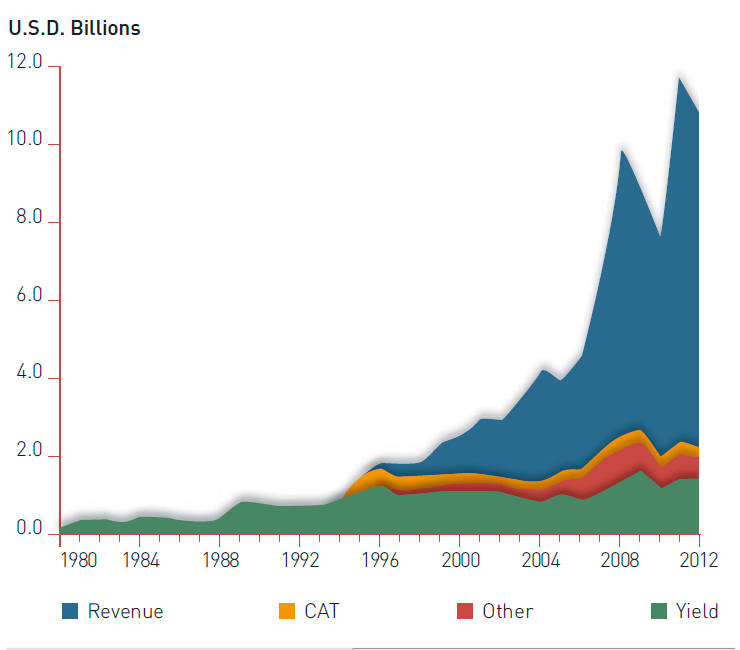

With the advent of the Great Depression, in combination with severe losses to agriculture during the Dust Bowl1 era of the 1930’s, Congress authorized the Federal Government to offer crop insurance directly to farmers. Other farm support programs were introduced in the same period with the intent to limit production, raise commodity prices, and stabilize farm income. The crop insurance program proved to be relatively unsuccessful in the ensuing decades, with low participation leading to ongoing political pressure for government-funded disaster assistance programs. By 1980, it had become apparent that reforms were necessary to increase farmer participation, provide a better spread of risk, reduce costs, and limit demand for free disaster assistance. To help achieving those objectives, private sector insurers were allowed to market and service the Federal crop insurance program in exchange for an opportunity to earn a profit through bearing a portion of the risk, through a program called Multi-Peril Crop Insurance (MPCI). Congress simultaneously introduced premium subsidies to make the program more affordable to farmers. These changes led to a rapid increase in insured acreage from 26 million acres in 1980 to more than 100 million acres in 1990. Despite this success, the program still fell short of its participation objective and failed to eliminate calls for disaster assistance. In response, Congress enacted the Federal Crop Insurance Reform Act of 1994. A key feature of this legislation was a requirement for farmers to purchase crop insurance in order to retain eligibility for other government farm programs. Premium subsidies were increased substantially to encourage greater participation, and a minimal level of free catastrophic risk protection, known as “CAT” coverage, was made available for insured crops. Free catastrophic risk protection was also made available for crops not insurable under the Federal crop insurance program. Following these changes, the insured area surged from 100 million acres in 1994 to 220 million acres in 1995.

Private sector insurers at one time had offered multiple peril crop insurance, but the effort floundered due to the difficulty in setting adequate rates to cover losses resulting from widespread crop disasters

In 1995, Congress removed the linkage between crop insurance and other farm programs. Insured acreage declined over the next several years, not exceeding the 1995 level until 2004. At the same time, insured liability and premiums grew substantially following the introduction of revenue protection insurance in 1996, which quickly became the preferred form of risk protection. The crop insurance program has continued to expand in recent years and currently provides protection for more than 100 crops, as well as cattle, swine, clams, and oysters.

Types of MPCI protection

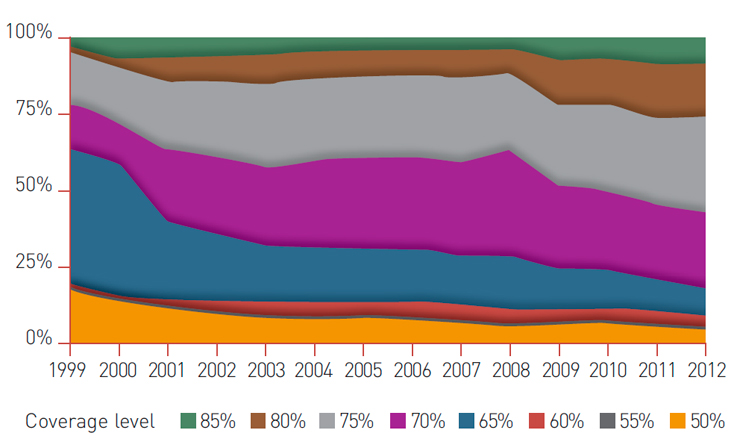

The products offered through the Federal Crop Insurance Program have continued to expand and evolve over time, including the Yield Protection (YP) program, introduced in 2011. YP is a type of individualized protection that pays the farmer for his or her production shortfall whenever the actual production on an insured unit of land falls below the farmer’s guarantee. Coverage is provided against natural causes of loss such as drought, excessive moisture, hail, wind, frost, insect damage, and disease. Farmers are required to follow good farming practices in order to reduce the risk of moral hazard. The guarantee is based on the farmer’s own average historical yield, known as the APH, for the intended farming practice on the insured land. More specifically, the guarantee is the product of the farmer’s APH, the number of insured acres, and the selected coverage level, which can range from 50 percent to as much as 85 percent in increments of 5 points. Since the policy pays claims only if actual production falls below the guarantee, the first portion of any production shortfall represents the farmer’s deductible. The price used to compensate the production shortfall is established in advance of the planting period based on daily settlement prices for futures contracts offered on the Chicago Board of Trade or other commodity exchanges.

RMA develops policy language for the various insurance products, establishes the rates, and develops the loss adjustment procedures that companies use to settle claims. Rates are intended to cover the risk portion of the premium only and exclude any provision for expense or profit

Revenue Protection is similar to Yield Protection, with the production guarantee again being based on the farmer’s own historical yields. The difference is that the value of the harvested crop is determined by multiplying actual production by the price at harvest rather than the price established prior to planting. This serves to protect the farmer against the additional risk of price decline between planting and harvest. The most commonly purchased type of Revenue Protection also provides protection against price increases. The purpose for this coverage is to protect the farmer in situations where the crop is sold prior to harvest. If the crop were to fail, the farmer would still be obligated to deliver an equivalent amount of production to the buyer or to compensate the buyer for the cost of purchasing the crop on the open market. If crop prices have increased over the year, the cost of purchasing the crop on the open market could exceed the amount the farmer received from the earlier sale of the crop.

Source: NCIS

By reducing marketing risk, this form of Revenue Protection allows producers to better manage their marketing activities in order to maximize farm revenue.

Several additional types of protection are available through the Federal Crop Insurance Program. Group Risk Protection and Group Risk Income Protection are comparable to Yield Protection and Revenue Protection except that the guarantee and the actual production in a year are based on county data rather than an individual farmer’s own experience. These plans tend to be purchased primarily in regions where farmer yields are highly correlated with county yields. The Adjusted Gross Revenue and Adjusted Gross Revenue-Lite plans of insurance establish the guarantee based on the farmer’s five year average historical revenue as reported on his Federal tax forms, with the indemnity based on the difference between the guarantee and the farmer’s current year revenue. These plans are available for farmers who want to insure a variety of crops along with farm animals and animal products, some of which may not be insurable under other forms of protection. The Rainfall and Vegetation Index plans of insurance provide indirect protection for animal forage by compensating the farmer for inadequate rainfall or insufficient green vegetation within a predetermined region through the use of local weather station or satellite data. Other plans insure the trees on which citrus and similar crops are grown, separately from insuring the crop itself.

Role of the U.S. Government

The Risk Management Agency (RMA) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture has regulatory authority over the MPCI program. In its role as regulator, RMA has several distinct responsibilities. To meet its public policy responsibilities, RMA develops policy language for the various insurance products, establishes the rates, and develops the loss adjustment procedures that companies use to settle claims. Rates are intended to cover the risk portion of the premium only and exclude any provision for expense or profit.

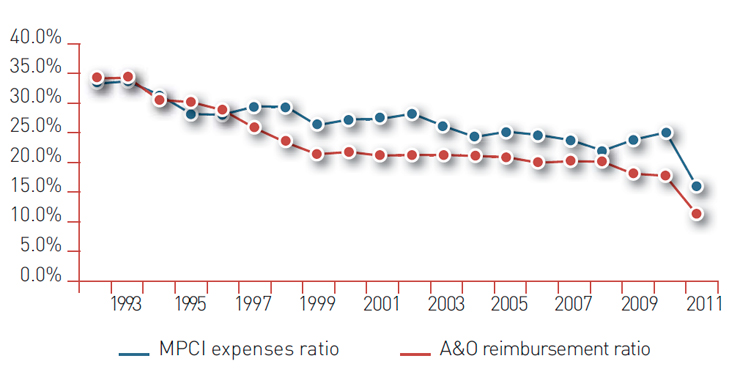

Second, RMA has the responsibility for providing subsidies to make the program more affordable to producers. This is accomplished through a second entity, the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC), which has the legal authority to obtain funds as needed from the U.S. Treasury. Premium subsidies are administered as a discount to the published rates rather than as a direct payment to farmers. Since rates exclude any loading for expense, insurer expenses are compensated through a separate payment, known as the Administrative and Operating (A&O) reimbursement. In recent years, the A&O reimbursement has fallen well below actual industry expenses.

Source: NCIS

A third RMA responsibility is to provide oversight of the seventeen Approved Insurance Providers (AIPs) that currently deliver the program. RMA monitors the AIPs to ensure that they have sufficient resources to meet their financial obligations, as well as to ensure compliance with all relevant laws, regulations, and procedures. Companies are required to use the RMA policies, rates, and procedures without modification, and are obligated to sell policies to any eligible farmer regardless of risk. RMA preempts all direct state regulation of the Federal Crop Insurance Program, while the Insurance Departments of each State retain responsibility for solvency and financial regulation of the AIPs.

The final RMA responsibility is to function in the role of a reinsurer. This serves two distinct purposes. First, it enables AIPs to cede most of the risk on those policies that AIPs are obligated to sell but that fail to meet AIP underwriting standards or are viewed as being unprofitable or commercially uninsurable. In the absence of this protection, universal private sector participation in the program would be infeasible. Second, it provides protection against widespread catastrophic losses that could exceed the financial capacity of an individual company. AIPs can also choose to purchase additional reinsurance protection in the commercial markets.

Operation of the program (SRA)

Each AIP signs a financial arrangement, known as the Standard Reinsurance Agreement (SRA) that specifies the financial terms under which the company delivers the program to producers. The terms of the SRA are renegotiated between RMA and the AIPs every five years. The most recent SRA went into effect for the 2011 reinsurance year. The government assists the farmers and the insurance industry through three types of financial support.

First, the government acts as a reinsurer of some of the risk insurance companies assume when they write MPCI insurance. In particular, the SRA provides three layers of government-provided reinsurance.

Since rates exclude any loading for expense, insurer expenses are compensated through a separate payment, known as the Administrative and Operating (A&O) reimbursement. In recent years, the A&O reimbursement has fallen well below actual industry expenses

The initial layer consists of pro rata coverage. Shortly after it issues a policy, the AIP assigns the policy to either the Commercial Fund (CF) or the Assigned Risk (AR) Fund. Each state has its own CF and AR fund. Companies use the AR fund to place the unprofitable or commercially uninsurable business; CF is for the more acceptable risks. Companies retain 20% of the liability, premium and indemnity in the AR fund. Companies decide what percentage they want to retain of the liability, premium and indemnity in the CF - and they can make separate decision for each state. In general, AIPs retain almost 100% of the business placed in the CF.

The second layer consists of government-provided non-proportional coverage. Companies pay no premium for this reinsurance layer – retained premium is identical to the retained premium after the first layer of pro rata reinsurance. In place of premium, FCIC takes a share of the underwriting gains to help pay for the reinsurance of any underwriting losses. For a given state and fund, FCIC determines the company’s retained underwriting gain or loss after the first layer of pro rata reinsurance. This amount is then subdivided into the underwriting gain or loss falling into each of seven loss ratio ranges (0-50%, 50-65%, 65-100%, 100-160%, 160-220%, 220-500%, and > 500%). A different sharing percentage applies to each layer. For the CF, the sharing percentage differs for the five Corn Belt states of Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Minnesota, and Nebraska as compared to all remaining states. This distinction, which was established in the 2011 SRA, allows FCIC to retain a larger share of the underwriting gain in these five states.

The final layer of government-provided reinsurance is known as quota share. This takes a fixed percentage of the liability, premium, and net underwriting gain remaining after the second reinsurance layer. This is similar to the first layer of pro rata reinsurance but, unlike the first layer, provides no benefit to the AIPs or the program. This can be interpreted as a mechanism to enable FCIC to recapture a portion of the industry underwriting gains.

The cost effectiveness of the industry has improved remarkably over time as the program has grown, despite increasing governmental requirements and continual changes in the program. Over the same period, the A&O reimbursement has declined to an even greater extent, with total payments in the latest year of 11.5% in comparison to actual expenses of 16.2%

Second, not only does the government reinsure some of the industry’s risk, but it keeps premiums low by assuming all industry operating costs. In traditional insurance, premiums are meant to cover the claims the industry paid as well as the costs insurance companies incur to deliver insurance (i.e., overhead, loss adjustment, and agent commissions). With MPCI, the premiums only cover the claims paid; as discussed above, the government separately pays the AIPs for what it believes is the cost of delivering insurance. However, in practice, the government payments do not cover all of these costs. The chart 3 shows industry expenses and A&O reimbursements by year, both expressed as a percent of gross premium. The cost effectiveness of the industry has improved remarkably over time as the program has grown, despite increasing governmental requirements and continual changes in the program. Over the same period, the A&O reimbursement has declined to an even greater extent, with total payments in the latest year of 11.5% in comparison to actual expenses of 16.2%.

Source: Grant Thornton database

Third, the government subsidizes the premiums farmers pay. These subsidies began with the 1980 Farm Act that instituted the modern crop insurance program. Initially, subsidies were set at 30% of a farmer’s premium for a policy at the 65% coverage level. Through subsequent legislation, the average subsidy has risen over time to its current level of 62% of a farmer’s premium.

Industry Participants

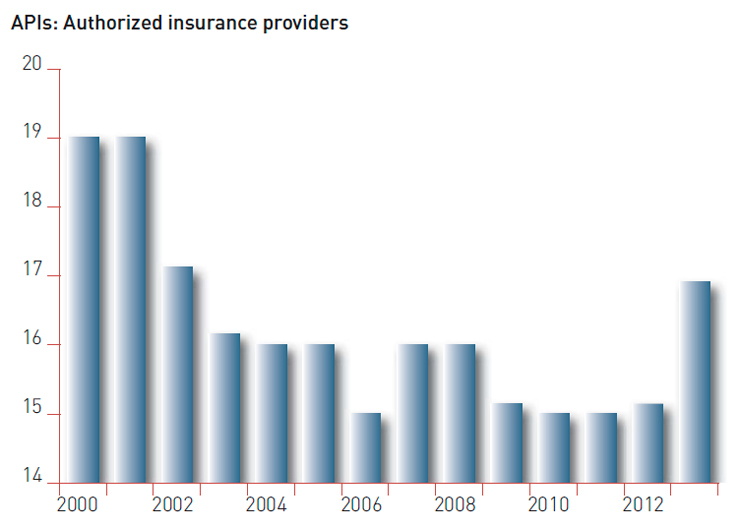

As discussed above, insurance carriers must be authorized by RMA to write MPCI policies. As shown in chart 4, while the number of approved insurance carriers increased in the 2013 calendar year, this number has fallen since 2000.

Source: Grant Thornton database

In addition to the companies that actually write the insurance contracts with farmers, reinsurance companies participate in the crop insurance industry by reinsuring a portion of the risk. These reinsurers do not need to be government approved.

Without the current economic support the government provides to farmers and the crop insurance industry, it is possible that the successes achieved by the program in delivering effective risk management solutions to U.S. farmers could be impacted

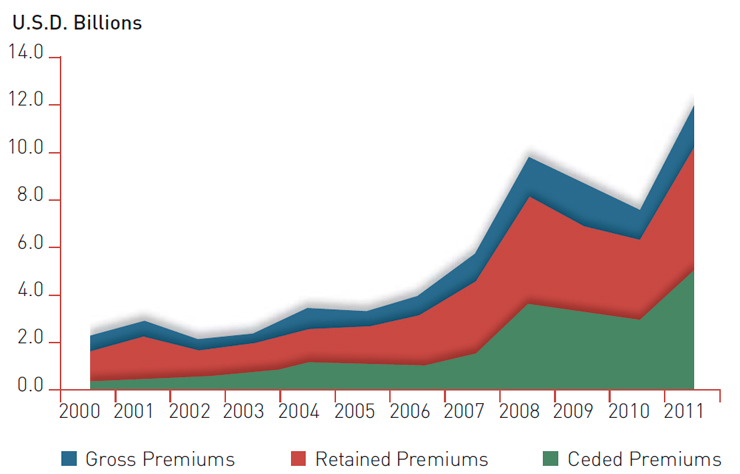

In chart 5, Gross Premiums represent the full amount of premiums companies charge farmers. Roughly 40 percent of the Gross Premium is currently paid by farmers and the remainder is the government premium subsidy. Retained Premiums are the premiums retained by the insurance companies after government-provided reinsurance. Ceded Premiums are the amount of Retained Premiums that the insurance companies reinsure in the commercial reinsurance market.

Source: Grant Thornton database

Chart 5 shows that commercial reinsurers’ participation in crop insurance has increased dramatically over the past decade.

Timeline of Payments

Due to government involvement in the program, payments are made differently in MPCI than in other type of insurance. In particular, cash flows to participating insurance companies are substantially delayed. To illustrate, we demonstrate the timeline that exists on crops that have a standard Spring planting season and Fall harvest season. Crops with different planting and harvesting seasons would be adjusted accordingly.

In March, the farmer purchases an insurance policy from an agent of one of the seventeen AIPs. The farmer pays no policy premium at this time.

In July, the AIP determines the premium for the policy based on the farmer’s planted acreage and pays agent commissions for the insurance policies they sold. The AIP would also bill the farmer at this time.

Later in July and August, the farmer pays the farmer’s portion of the premium required under the policy to the AIP. The AIP immediately forwards the entire premium to FCIC. FCIC makes an accounting entry to credit the government premium subsidy to the policy.

In October, FCIC pays the A&O reimbursement to the AIPs to compensate them for their delivery costs. In addition to these being less than the true costs, as discussed above, these payments are received after the AIPs pay their agents.

Some agencies that oversee items like Social Security and government debt payments were exempted from cuts. Payments to FCIC, which oversees crop insurance, were also exempted

Beginning in July and extending through harvest and into the following year, the AIPs settle claims for farmers who are owed money under their policies. Since the AIPs did not retain the premiums, the funds needed to pay each claim are transferred from FCIC to an escrow account maintained by each company.

If the AIP uses all of the premium that FCIC has credited to its account to settle claims, it must deposit additional funds into the escrow account to cover the cost of all subsequent claims. In effect, AIPs are obligated to pay FCIC for any underwriting loss as soon as it occurs.

If the AIP earns an underwriting gain, FCIC pays the gain to the AIP in October of the following year. Consequently, an AIP must wait an entire year before it receives the underwriting gain it earned in that growing season.

Recent Issues

There are two major issues that are currently affecting the crop insurance industry: recent droughts and proposed governmental legislative changes.

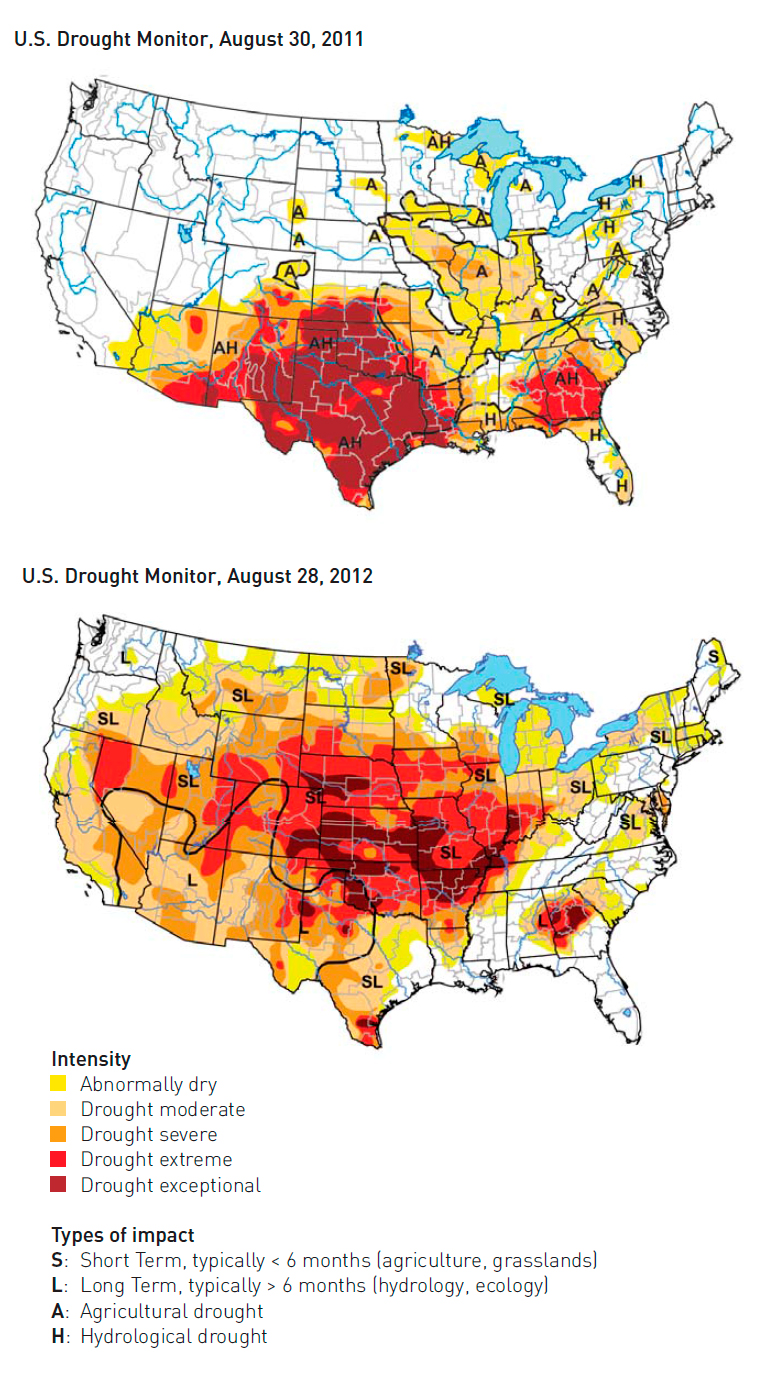

The United States experienced severe droughts in both 2011 and 2012. The most recent year with a drought of similar magnitude occurred in 1988. As shown in chart 6 below, different parts of the country were affected by the drought in each year.

Consequently, different crops were affected in each year. The 2011 drought was primarily centered in Texas and Oklahoma, causing a decrease in cotton production. The 2012 drought involved the Upper Midwest, which grows primarily corn and soybeans. Interestingly, wheat, which is also grown in the Upper Midwest, was not greatly affected in 2012 because wheat is planted in this region in autumn and harvested in late spring. The 2012 drought rapidly increased in severity from June to July and persisted into August, after most wheat had been harvested.

Source: http://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/

The risk associated with insuring crops can be demonstrated by the fact that, even though it was one of the driest and most unfavorable growing conditions in decades, 2012 was anticipated to be a banner year with expectations of record or near-record production. For example, in the first weekly rating of the corn crop on May 20th, over 75 percent was rated as good to excellent, while only 3 percent was in the poor or very poor category. By September 30, only 25 percent of the crop was rated good to excellent with 50 percent rated poor or very poor. Sharp declines in soybean ratings also occurred, with only 35 percent of the crop rated good to excellent as of October 7th, as compared with 65 percent in the year’s initial weekly soybean rating on June 3rd.

As a result of the recent droughts, farmers’ behaviour could change in 2013 and beyond. For example, a greater use of drought resistant hybrids could occur in 2013. Also, farmers might plant more soybeans as opposed to corn since soybeans is able to produce a crop with less moisture.

In addition to the recent droughts, the crop insurance industry also needs to be concerned about potential legislation affecting the crop insurance program. The Farm Bill is a comprehensive piece of legislation that covers most government policies related to agriculture in the US. The 2008 Farm Bill expired on December 31, 2012. When a settlement was reached to the so-called Fiscal Cliff crisis, the 2008 Farm Bill was not renegotiated, but rather was temporarily extended until September 30, 2013. Unless another extension is granted, a new Farm Bill must be passed by that time. Failure to pass a new Farm Bill would result in Federal farm policy reverting to the provisions of permanent law enacted in the 1930s and 1940s.

It is unclear how the government will handle crop insurance in the new Farm Bill. Some proposals have called for an across the board reduction in the premium subsidies the government provides; others only cut the subsidies for “large” farmers; some have no cuts at all. The U.S. Government instituted a sequester on March 1, 2013, which reduced spending by almost all government agencies. Some agencies that oversee items like Social Security and government debt payments were exempted from cuts. Payments to FCIC, which oversees crop insurance, were also exempted.

Without the current economic support the government provides to farmers and the crop insurance industry, it is possible that the successes achieved by the program in delivering effective risk management solutions to U.S. farmers could be impacted. Currently, 80 to 85% of eligible U.S. crops are insured. One of the primary advantages of the current crop insurance program over other types of farm support is that farmers contribute substantial sums as premium in order to obtain insurance protection designed around their individual needs. Other farm support programs are funded almost entirely by the Federal Government with little or no financial contribution from farmers. Agricultural related disaster aid cost the U.S. government approximately $45 billion between 1989 and 2001. However, thanks to the growth and success of the crop insurance program, there were no calls for Federal disaster aid in either 2011 or 2012 despite the severity of droughts in each year. The crop insurance industry delivered on its promises to protect farmers against drought and other perils, and delivered those benefits rapidly, accurately, and at relatively little cost to the U.S. taxpayer. The U.S. crop insurance program has demonstrated that farmers are willing to commit their own money to obtain a program that truly meets their Soya harvest needs both today and in the years to come.

1 Dust Bowl: Environmental disaster in U.S.A. caused by 1932-1939 drought that affected plains and grasslands ranging from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada. The dust bowl effect was compounded by years of land management practices that increased their susceptibility to wind action, since, lacking moisture, was lifted by the wind in great clouds of sand and dust so thick they hid the sun. The Dust Bowl multiplied the effects of the Great Depression in the region and caused the largest population displacement occurred in a short space of time in U.S. history.