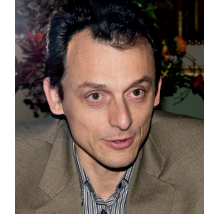

Pedro Duque: General Manager of Deimos Imaging and astronaut on reserve leave of the ESA (European Space Agency)TECHNICAL

Pedro Duque was born in Madrid on 14th March 1963. He graduated from the Polytechnic University of Madrid (Higher College of Aeronautical Engineering) with a Degree in Aeronautical Engineering in 1986. It was at this point that his career became meteoric. He started working as an intern in GMV (Flight Mechanics Group) and was appointed to the European Centre of Space Operations (ESOC) of the European Space Agency (ESA) in Darmstadt (Germany) shortly afterwards. He worked in the Precise Orbit Determination Group, participating in the flight control team for two ESA satellites, until 1992.

In May 1992, he was selected for the ESA’s Astronaut Corps. He underwent Basic Training at the European Astronaut Centre (EAC) in Cologne (Germany) and then attended another course at the Russian TSPK astronaut-training centre, in Star City, as part of a project designed to establish open cooperation between the ESA and the MIR Russian space station. Upon his return from Russia in 1993, he began to prepare for the joint ESA-Russia Space Mission called “EUROMIR 94”, receiving the official qualification of Scientist- Astronaut for the Soyuz and MIR spacecraft. He was selected as a member of the reserve crew and ground communications coordinator liaising with Russia for the EUROMIR 94 space mission in May 1994. In 1995, he trained in Star City to support the joint ESA-Russia “EUROMIR 95” space mission. He was appointed Reserve Scientist-Astronaut for the Life and Microgravity Spacelab mission that same year.

In 1996, Pedro Duque trained as a NASA Flight Engineer and began working at the Johnson Space Centre. In early 1998, he was appointed member of the crew of the STS-95 Space Shuttle Flight, in a joint mission for NASA, the ESA and the Japanese Agency NASDA. On 29th October 1998, Pedro Duque went into space for the first time, as a Flight Engineer of the “Discovery” Space Shuttle. Between 1999 and 2003, he worked on the European components of the International Space Station, in the European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC) situated in Noordwijk (Holland). He was among the first set of European Astronauts to qualify with advanced training in 2001 and he was Flight Engineer for the Cervantes Space Mission between 18th and 28th October 2003.

Pedro Duque has participated in four spaceflights, all related to scientific research, which makes him an expert in adapted space experiments. After his last spaceflight, the ESA appointed him Operations Director of the Spanish User Support Operations Centre for the International Space Station, which is part of the “Ignacio da Riva” Microgravity Institute of the Polytechnic University of Madrid.

Pedro Duque has been on leave of absence from the ESA since October 2006, although he remains on standby should he be needed. Among other special honours, he has received the Russian Federation’s “Order of Friendship” from President Yeltsin (March 1995) and the Great Cross to Aeronautical Merit from HM the King of Spain (1999). He has been a Member of the Royal Engineering Academy of Spain since April 1999. Along with another three astronauts, he received the Prince of Asturias Award for International Cooperation in October 2009.

"There is a great accumulation of risks in the space" Pedro Duque, the first Spanish astronaut to visit space and employee of the European Space Agency (ESA), reveals himself to be a person of simple pleasures, who is passionate about space and adept at overcoming great challenges. Here, we join him to review some of the milestones and myths of the space race and learn more about the international aeronautics and space industry, in which Spain has been playing a role for more than 20 years, thanks to its involvement with the ESA. As General Manager of the first completely private European company to put its own satellite into orbit and sell its Earth imaging services, he provides us with some interesting facts.

How did you first develop an interest in space

and when did you first feel the desire to become

an astronaut?

I’ve always had an interest in aeronautics, even

from my childhood. The reason is simple: my

father was an air traffic controller and we have

always shared an interest in aeroplanes. He

used to take us to the control tower, in the

airport. I even tried the flight simulator once,

one of those that pilots use to train. Undoubtedly,

this spurred my interest in aeronautics and

encouraged me to become an aeronautical engineer

and it was a small step from there to

developing an interest in space.

How did you first get the chance to become an

astronaut?

When I was finishing my degree, the government

approved a new Law on Science, under

which Spain would begin to take part in international

R&D (Research and Development)

projects and become more involved in international

programmes and agencies. One of these

organisations was the European Space Agency

(ESA) and one of the selected laboratories was

the one at the university where I was working

as a research fellow. We formed a group that

began formalising contracts with the ESA. The

opportunity came about because the Spanish

Government began to allocate more resources

to international projects from that moment

onwards, which would come back in the form

of contracts with the industry; some of the

other aeronautical engineers and I became

converts to aerospace engineering.

The first time you look through the window and see Earth, with its dark horizon and the Sun, is indescribable.

How were you selected from the different candidates

wanting to work at the European Space

Agency?

Let me tell you a story: when the results of the selection process were about to be published I

began to receive calls from all the radio stations

and TV channels, even before anyone contacted

me officially. The authorities in charge of the

selection process inform the government first

and afterwards the candidates. But there are

so many people involved in the process that any

news always gets leaked.

When did you first travel to space?

I first travelled to space on 29th October 1998.

I spent a year in Russia before that. I lived in

Star City, a small village with only 5,000 residents

and the location of the space training

and research facility, with its technicians and

engineers. The place has restaurants, schools,

cinemas, everything you might need to make

life pleasant for the people living there, because Star City was the product of Soviet planning,

which, at least where questions of space were

concerned, was autarchic.

Where else can ESA astronauts receive training?

The International Space Station is run by the

USA, Russia, Japan, Canada and the ESA, representing

many European countries. All these

countries have centres for training astronauts.

Right now, anyone who is going to spend any

time in the Space Station has to learn how it

works, and each centre specialises in one field,

which means that the trainee has to pass through

all of them. This means that they spend their

lives travelling.

Moving on to sensations, how does it feel to

see the Earth from space?

It is incredibly overwhelming, even though we

all receive training and are fully prepared for it.

Obviously, we have seen the photographs and

videos before we embark on a mission and we

receive training so that we are prepared for the

fast movements onboard the spacecraft. And if

there is anything to see below, the onboard

computer will tell you exactly where it is. Even

so, it is awe-inspiring. The first time you look

through the window and see Earth, with its dark

horizon and the Sun, an indelible memory is left.

What do you think of during those moments?

I do not know what to say, to be honest. All the

preparation and training teaches you to detach

yourself from the situation, to feel as little as

possible. I usually compare it to people who

climb mountains: they make a titanic effort to reach the peak, they look around, do whatever

it is they have to do there and come back down

and they do not think about it too much.

What should humanity’s immediate objectives

in space be?

I don’t see any specific objectives as such. But

it is all justified by the desire to explore, to

transcend the barriers of knowledge, by the step

forward that it represents for the human race,

for a country or for a society. This is a special

year because on 21st of July, we celebrated the

40th anniversary of man’s landing on the Moon.

At the time of the landing, there was a lot of

momentum behind the exploration of space, for

various reasons. One of them was that the US

wanted to be the first country to reach the Moon

and so there were numerous experiments on

weightlessness or zero gravity, involving many

different fields: physics, medicine, biology. There

was a whole series of experiments on the effects

of gravity. Because of these experiments, we began to research how cells relate to each other,

how life comes about, how we have evolved, how

materials behave. And there are many other

benefits that we take for granted now that would

not have been possible without space exploration

and research. As an example, we now have

satellites that transmit information practically

in real time; in other words, any news or any

developments are disseminated instantaneously

and this gives us an overall view of the world,

which has revolutionised the way in which we

understand the world and relate to one another.

We are no longer as isolated as we were. We

know that any event happening at any time,

anywhere in the world, can be reported on the

news in a matter of hours and we take this for

granted. The same applies to travelling using

GPS. We can act as though navigation is no

longer a problem. Why? Because we have managed

to create a system, a network of 48 satellites

in space. And we have also managed to

carry large and heavy cargo into space.

What is it like living with other astronauts in

space?

It is difficult, because you are in a very small

space and you have to share everything. It is

like crossing the Atlantic in a small sailing

boat. You would be short of space. There are

specific needs that have to be met when you

are living so close together and everyone has

to adapt to each other.

What do you think about tourism in space for

those that can afford the trip?

It is like everything else in life. Initially, only

people with a lot of money could afford to buy

a ticket to board a plane. As the industry grew

and received finance, it began to design more

efficient and comfortable planes, finally creating

a form of mass transportation. The same has

happened with many of humanity’s inventions.

The first cars were only available to the wealthier

upper classes. Thanks to the large amounts of

money paid for these cars, the factories were able to invest money in R&D, allowing them to

make more efficient vehicles that were then

accessible to more people.

Which countries are currently the dominant

players in space?

The US is still the superpower in space, at least

for the moment, followed by Russia, which specialises

in the construction of rockets that can

carry very heavy cargo into space. Progress in

Europe is not as efficient and very difficult, but

that is to be expected, as ten times less public

money is allocated to space programmes in Europe.

We do stand out in the areas in which we

specialise and we are on a par with the US or

Russia in that sense. For instance, the European

cargo rocket easily competes with the American

or Russian, although the Russian cargo rocket

is probably more cost-efficient.

I was at the last International Astronautical

Congress and learnt that India is only waiting

for the Authorities to sign the necessary documents

before it implements its own astronaut

training programme and anything else that is

needed. The only problem in the US is that space

exploration budgets began to decline in real

economic terms months before Armstrong even

stepped on the Moon and they have been falling

steadily ever since.

Perhaps that is because there are more pressing

problems on Earth, such as fighting hunger,

disease or providing education, for example.

Of course, I agree, but the only way to solve

many of these problems is through R&D. As an

example, I would cite the extensive research

into climate change and the fact that we now

know a lot more about it thanks to the observation

of the planet from space. It is also true that

the current lack of funding in the western sphere

has meant that other great powers, such as

China, have been able to catch up and meet the

challenges of space exploration with very little

funding, but this is also thanks to the fact that

they have had access to the knowledge and skills

that other countries developed beforehand

through experimentation and research.

The USA and Russia have been investing in space

exploration and research for the last 50 years,

under the belief that it ultimately boosts the

self-confidence of a nation. It constitutes an

enormous stimulus to education and training.

People perceive that their country is at the cutting

edge of something as thought provoking and awe-inspiring as outer space. The US is a world

power because it dominates space. China and

India have taken note of this.

Space tourism is no different to what humanity has experienced with other inventions.

What would you say is the key to the USA’s

dominance of the space race?

The USA is sufficiently open to public debates as

a country. Where space exploration is concerned,

we have yet to see what President Obama’s approach

will be. Nevertheless, the US is the most

technologically advanced country in the world and

should be able to put a man on Mars in coming

years. It is also a question of budgets: NASA received

only 0.5% of the US’s Federal Budget this year,

which is not very much, but it is still 10 times more

than the sum invested in Europe. If there is something

that needs to be done industrially, it can be

done in the US, which is currently the benchmark

country. Until 20th January, the US refused to

partner or collaborate with any other nation for

the project of establishing a permanent base on

the Moon by 2020. Now it is all up in the air.

Clearly, the US’s policy with regard to space is to

consolidate its dominant position, although it is

open to cooperation where certain matters are

concerned.

A private satellite that makes history

As an astronaut turned businessman, how does

the corporate world compare with your experiences

of physical risk in space?

There are similarities. Though I must emphasize

that the company is not mine, I am only the Managing

Director. In space programmes, the astronaut

is up there, at the top of the system, which

means that everyone looks to you for advice.

However, the experience of being an astronaut,

of living in space, gives you a certain approach,

where you are more prepared to listen to others

than to establish strict chains of command.

Tell us about Deimos Imaging and where the

capital came from.

Deimos Imaging is the first fully private European

company to operate its own Earth Observation

space satellite. The share capital came from a

Spanish corporate group, called Elecnor. The

group founded a company 7 years ago, called

Deimos Space, which employs young engineers

from Spain and carries out work for the European

Space Agency. Deimos Imaging is an offshoot of

that initial company.

Given that the Deimos project creates added value

through R&D&I (Research, Development and Innovation),

how far would you say Spain has come?

How strong is the Spanish aerospace industry?

Spain first began to contribute to the European

Space Agency about 23 years ago. Since then, the

country has built and consolidated an aerospace

industry. Initially, our share in the project was

only 5%. It is currently 7% and will reach 10% in

the future. It would be almost impossible to have

a 100% share. Spain fits in well in certain niches.

We have between 2,000 and 3,000 employees who

are 100% dedicated to space work. There is a lot

of uncertainty at the moment, because it is difficult

to predict how things will develop or determine

whether it is best to cut spending in the light of

the financial crisis or to boost investment in R&D&I

on the supposition that it will help us come out of

the crisis sooner. Nevertheless, the aerospace

industry could find itself in a better position.

Can the European Galileo project help Spain’s

aerospace industry?

It is helping. Spain has a share of 10% or more

in the project. In fact, our company manufactures

the most critical computers within the whole

Galileo system. They are built in Tres Cantos, on

the outskirts of Madrid. Some extremely difficult

and critical tasks are allocated to Spain, which

is proof of our enormous potential.

Obviously, Deimos Imaging has carried out its

viability studies, knowing that it will be competing with other companies that provide similar

services. What would you say constitutes Deimos

Imaging’s competitive advantage?

Obviously, there are already Earth Observation

Satellites in space, but these are used for experiments,

as prototypes. What we have done is

design a satellite that can take images that are

much larger, but more importantly, that can

take them much more frequently. This creates

more opportunities as we can monitor Earth

more intensively. The satellite was launched in

mid-July 2009, using a Russian rocket called

the Dnieper, which is an intercontinental ballistic

missile adapted for these purposes, which has

been used and tested extensively.

Everyone is waiting to see the quality of our

images before signing any contracts. Our satellite

Deimos-1 rotates around Earth, from pole

to pole, at a height of 600 kilometres. The satellite

has a guaranteed life of 5 years, but satellites

from the same series have lasted longer, between

8 and 10 years. It all depends on how we

treat it. I must clarify that we purchased this

satellite as a capital good and that the added

value comes from the applications that we have

developed and the quality of these applications.

The monitoring base is situated in Boecillo,

Valladolid. We have invested approximately 30

million euros in the whole project.

What is the expected ROI?

If it is positive, it will be a great achievement.

What can you tell us about the insurance schemes

that are developed for these space programmes?

There is a great accumulation of risks in space,

obviously, because you are pushing technology to its

maximum limits. The margins of error in our designs

are very narrow, less than 5%. Evidently, we need

insurance. It is essential whenever you embark on

a space project and it is great that we can find insurers

that specialise in insuring space projects in Spain.

Deimos Imaging is the first private European company to operate its own Earth Observation Satellite.

a. Sputnik Satellite

b. Front Page: Yuri Gagarin, fist human

in space

c. Buzz Aldrin's footprint on the moon

d. Skylab Space Station

NASA/courtesy of nasaimages.org

Milestones in the Conquest of Space

- 4th October 1957. The USSR launches the first Earth-orbiting artificial satellite, called Sputnik I. It remains in orbit for three months, circling the earth every 96 minutes. Sputnik II would later take the dog Laika into space.

- April 1961. The Russian cosmonaut Yuri A. Gagarin is the first man to see Earth from space, on board the Vostok 1 spaceship.

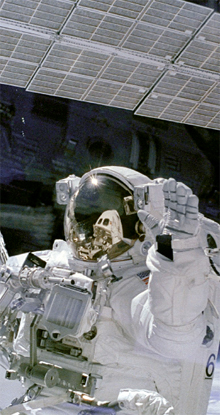

- March 1965. The Russian cosmonaut Alexey A. Leonov is the first human to conduct a space walk.

- 1966. The Russian spacecraft Luna 10 lands on the Moon.

- 20th July 1969. Man walks on the moon. The feat is achieved by American Astronauts Neil A. Armstrong, E.E. Aldrin and M. Collins, as part of NASA’S Apollo 11 mission.

- 1971. The first manned orbital space station, the Russian Salyut 1, is launched. The crew spends three weeks in space but perishes on re-entry to Earth.

- May 1973. The US puts the first space laboratory, called the Skylab, into orbit; three different crews will visit the station.

- 1986. The first module of the Russian MIR (Peace) space station is put into orbit; the station will remain operative for 15 years.

- 1995. The Russian cosmonaut Valeri Polyakov breaks the record for the longest period spent in space by man. He spends 438 days in the MIR space station, between January 1994 and March 1995.

- November 1998. The first module of the International Space Station, in which 17 countries are involved, is put into orbit.

- 9 space missions take place between 2000 and 2004. The new century sees the space race accelerate, with numerous space missions. At the same time, new projects with ambitious objectives are developed, such as the installation of a permanent base on the Moon or a manned space mission to Mars.

For more information, please visit: http://www.conquistadelespacio.net