You are in:

- Start

- Interviews

- Ricardo García Herrera. President of the Spanish State Meteorological Agency, AEMET. Madrid - Spain

Ricardo García Herrera. President of the Spanish State Meteorological Agency, AEMET. Madrid - SpainNATURAL PERILS

Ricardo García Herrera was born in Valladolid in 1958 and holds a Doctorate in Physics from the Complutense University of Madrid, where he is also a Professor. He is a graduate of the IESE Management Programme as well. He considers himself to be a climatologist –an expert on climate– with extensive experience in the analysis of climatic variability and its impact on public health. His career has been a mixture of university life and the field of management and public institutions. He started working at the age of 22 as an assistant at the Complutense University and took advantage of those early years to write his doctoral thesis on air pollution models. In addition, he also specialised in the environment and public health, which led him to leave his work mark on various bodies in the Autonomous Regions of Castile and Leon, Navarre, the Basque Country and Madrid. He went on to become the Director of Public Health for the Basque Government and Director-General for Prevention and Health Promotion of the Regional Government of Madrid.

Ricardo García Herrera is the author of more than 80 scientific and research articles published in international journals and he has also written various books. He has coordinated numerous national and international research projects and also the Master’s Degree course in Geophysics and Meteorology at the Complutense University. He has been a contributing author to the IPCC’s Fourth Report and represents Spain on different international programmes. He was appointed President of the Spanish State Meteorological Agency, AEMET, at the suggestion of the Ministry for the Environment and Rural and Marine Affairs on 12 February 2010.

“The future depends on improving weather forecasting and offering more climate information”Concerns about weather and climate have become two constants in our lives, supported by ever more precise and accurate forecasting models. Learning first hand about the objectives and daily work of Spain’s State Meteorological Agency, as well as its most pressing challenges, from the words of its President is a real treat on account of both the information provided and the simplicity with which its development over 125 years is explained.

Broadly speaking, how was the historical

development of meteorological services in

Spain up to the establishment of the State

Meteorological Agency?

AEMET is the continuation of an organisation

which in 2012 will formally be 125 years old,

although its origin is even older. It became

a State Agency at the beginning of 2008, and

so we are a bit like a Directorate-General,

but with more competence; for example, we

have some degree of freedom as regards the

management of resources, be they budgets

or personnel.

In Spain, meteorology arose from astronomers

who, depending on weather events,

like the presence or lack of clouds, could

observe the sky. The beginnings were in some facilities at El Retiro Park in Madrid,

and for a long time a strong statistical approach

involving tables of meteorological

data prevailed, but this offered little forecasting

capability. This led to a delay of

about 40 years in the creation of Spain’s

Meteorological Service compared with

those set up in the UK, Germany or France,

a lag further aggravated by problems relating

to the competencies and capacities

of local bodies and bureaucracies. Finally,

the Central Meteorological Institute

was merged with the Retiro Observatory.

These facilities still exist and now belong

to AEMET. Until 1976, the organisation was

called the National Meteorological Service

and was dependent on the Air Ministry. It

was then run by the Transport Ministry and

was called the National Meteorological Institute.

Finally, it depended on the Ministry

for the Environment and Rural and Marine

Affairs and, through the Secretary of State

for Climate Change, became the State Meteorological

Agency (AEMET) and assumed

all the competencies of the former National

Institute of Meteorology (INM).

Our functions are to protect people and property by forecasting the weather and supporting environmental and climate change policies

What are AEMET’s mission and roles?

We are an atypical agency because although

the main mission of meteorological agencies

and services is to help protect people

and property by forecasting the weather,

we combine other functions, like supporting

environmental and climate change

policies. This means that, besides making

short- and medium-term forecasts, we

produce climate scenarios which can be

accessed on our website. We support environmental

quality policies by, for example,

designing air-quality forecasting models.

We also manage the Spanish background

pollution monitoring network. This means

that we have about twelve sensors installed

outside cities which are not disturbed by the

emissions from any big city and help us to

measure the background pollution and also

the transboundary transport of air pollutants.

AEMET is not an organisation dedicated

to R&D –research and development–

but it needs to be up to date, as we use very

advanced technologies such as space- and

ground-based remote sensing.

We are also the government body for matters of international cooperation on the

subject of meteorology and climate. We

maintain two very active programmes, one

in Latin America and the other in Western

Africa.

What resources do you have?

We have about ninety workplaces and a staff

of 1,300 highly-skilled people who fit three

types of profiles: meteorologists, who carry

out development and management tasks;

graduates, most of whom are in charge of

weather forecasts; and then observers, who

take care of operating and maintaining the

observation network. A third of the staff are

located at our headquarters in Madrid. The

rest are integrated into seventeen territorial

delegations, one for each Autonomous Region,

and we also have eleven forecasting and

monitoring groups. These groups manage

warnings and forecasts from the regional

point of view. There are also personnel in all

observatories, air bases and airports.

What weather hazards can threaten a territory

like Spain?

Given our characteristics, what worries us

now is a phenomenon which is very difficult

to predict: storms and what is commonly

known as “gota fría” (literally: “cold drop”),

which is actually an atmospheric structure

in which cloud systems that are small in

size and short-lived develop but cause very

intense precipitation. With these characteristics,

it is very difficult for a forecasting

model to give a sufficiently accurate warning.

We are making efforts to downscale our

predictions.

AEMET is not an organisation dedicated to R&D –Research and Development– but it needs to be up to date, as we use very advanced technologies such as space- and ground-based remote sensing

How is your forecasting system organised?

Thirty-five years ago, various European

meteorological services decided to combine

forces and create a centre of excellence for

making very good medium- and long-term

forecasts: the European Centre for Medium-

Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) in

Reading in the United Kingdom, which

is rated the best in the world. The

ECMWF provides two daily forecasts on a

hemispheric scale, at midnight and midday,

with a resolution of about 15 kilometres. We

then use this information to run our own

high-resolution model for two areas – one

centred on the Iberian Peninsula and the

other on the Canary Islands – to release four

daily forecasts. All AEMET products such as

warnings and different types of forecasts

are produced from these models. What we

are now working on is to increase the ten- or

fifteen-kilometre resolution of the current

models to a one-kilometre resolution, which

will be available in 2013 or 2014.

Does a weather forecast accurate to a kilometre

not seem very ambitious?

Yes, it does. The strategic plan approved

last June for the ECMWF includes the aim of

getting down to the one-kilometre scale, but whereas the Centre proposes achieving this

by 2020, we want to get ahead of that date

with our model at the Agency. To do this, we

are going to get a new supercomputer which

is going to entail considerable expenditure

but will allow us to optimise the complexity

of the calculations that need to be made.

One of the specific features of meteorology

is that it presents situations which are very

difficult to predict, such as storms and fogs,

which have a very local effect and greatly

affect aviation. The movements of fronts,

however, are much more predictable.

What work are you developing in relation to

climate change?

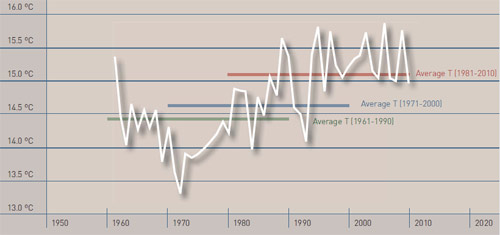

We are concerned with how the climate is

evolving. As part of a programme coordinated

by the World Meteorological Organization

(WMO), normal climatic conditions (see pp.

34) have been being measured since about

1970. For this, climate periods of 30 years

are used and we see how all the variables

develop, but especially temperature and

precipitation. We have twenty-seven topquality

meteorological stations devoted

to this, and these will support climate

change data in the medium and long

term. Precipitation patterns have not

changed since 1970, but temperature has.

Whereas between the periods 1961-1990

and 1971-2000 the average temperature in

Spain increased by 0.22ºC, it increased by

0.46ºC between 1971-2000 and 1981-2010,

doubling the observed variation between

the previous two reference periods.

Serious attention needs to be paid to this

question. It is not a prediction but a fact.

This will certainly trigger changes to the

water cycle. When it rains, the rainfall will

be very intense, and then there will be long

periods of drought.

The ‘gota fría’ is an atmospheric structure in which cloud systems develop which are small in size and short-lived but cause very intense precipitation. With these characteristics, it is very difficult for a forecasting model to give a sufficiently accurate warning

Do all meteorologists use your services? Is

it a driver for your marketing?

Some meteorologists use our services,

others don’t. AEMET’s priority is to be an

efficient public service. For example, we

have a new data policy. Until a year ago,

you had to pay to get the data. Now we have

decided that it is better for them to be freely

available on our website, where there is a

lot of information which is not shown only

in the form of graphs but also by means of

data files that can be used by professionals.

When you consider that citizens pay for the

content produced by AEMET through their

taxes, it is logical for that information to

go back to them. Secondly, we have learnt

that, by making it freely available, we are

helping the meteorological industry, which

is immersed in a process of improvement.

In the 1960s, forecasting was an art that

depended on the way the meteorologist on

duty had been trained. Currently, meteorology

basically depends on the interpretation

of models, making it much more systematic

and scientific. As there are many small users

with specific requirements, our role focuses

on the one hand on laying the foundations

so that anyone can obtain this information

and, on the other, on taking care of large

institutional users: civil defence, aviation and

the armed forces, for example. In the months

that this policy of transparency has been in

operation, users have downloaded around a

hundred thousand files per day from us. We

are the most-visited Spanish institutional

website, with around 3.5 million visits each

day, and the usage profile is growing. This is

the best quality control we can have.

Whereas between the periods 1961-1990 and 1971-2000 the average temperature in Spain increased by 0.22º C, it increased by 0.46º C between 1971-2000 and 1981-2010

In what way are you collaborating in the programmes

in West Africa and Latin America?

We are the World Meteorological

Organization’s foremost contributor for the

areas of cooperation, our contribution being

channelled through conferences in which the

directors of hydrometeorological services

take part. We are very keen in knowing their

needs and try to meet them. On this basis, a plan of action is set in motion using the

resources available to us at any time. We offer

training and exchange programmes and

courses, as well as access to some technologies,

like handling the output from the

ECMWF’s models; we also make Meteosat

images available. In the area of Africa

extending from Mauritania to Guinea, we

are carrying out three programmes: a

meteorological one to support fishermen;

another one dealing with meteorology and

health; and another focused on agriculture.

Four hundred metereological stations have

been set up, spread across various zones, in

order to help them take decisions on sowing

or watering. In addition, and more generally,

they are given forecasts for sand and dust

storms, which is something truly novel and

useful for this entire region.

What is your most immediate challenge?

Our main challenge is to get the new Climate

Services Site up and running as part of the

Agency’s new data policy. It is possible to give a lot of very useful climate information not

only through lists of data but also through

threshold values, projections, forecasts

or normal values, amongst other things,

so that each user can use the information

as required. This is so important that at

the WMO’s last congress in June, it was

suggested that an extraordinary congress

be held. Generally speaking, the European

meteorological services are going to

continue improving smaller-scale weather

forecasts and are going to provide more

climate information. This is an important

development for the whole world and we

are very well positioned for offering these

services.

How do you interrelate with insurance?

Our experience is basically linked to the

Consorcio de Compensación de Seguros

(Insurance Compensation Pool), to which

we supply the data they request on certain

climatic events that have a major claims

impact, such as windstorms or tempests.

| Reference period | Annual average temperature in Spain | Difference between two consecutive periods |

|---|---|---|

| 1961-1990 | 14,43 ºC | |

| 1971-2000 | 14,63 ºC | + 0,20 ºC |

| 1981-2010 | 15,09 ºC | + 0,46 ºC |

Variation in average temperature in Spain between the 1971-2000 and 1981-2010 reference periods [Source: AEMET “Note on the average variation in temperature and precipitation in Spain between the 1971-2000 and 1981-2010 reference periods”]

Our main task is to take note of what is happening with regard to climate change and to communicate it.

The use of satellites

Do you have your own satellites?

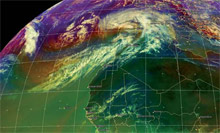

No country in Europe owns satellites. In

1986 the European countries decided to

create a consortium known as EUMETSAT,

with its headquarters in Germany, to operate

weather satellites at European level. It

combines various types of programmes:

the Meteosat programme, a set of geostationary

satellites which capture images of

Europe every 15 minutes; the polar satellite

programme, offering images of different

strips of the Earth on each pass; and then

there are others, like the Jason programme,

dedicated to monitoring ocean variations.

The satellites are launched from French

Guyana. Our participation is the fifth largest

in this consortium through Spain’s financial

contribution of eight per cent. This contribution

is made on the basis of gross domestic

product.

What has the use of satellites meant for

weather forecasting, and how long have

they been used?

The satellite images that we see on television

each day are the input data for obtaining

the weather diagnosis and forecast. In

fact, we could not make the planned jump

to a kilometre-scale forecast without the

help of satellites. Last year at EUMETSAT

they approved the construction of the thirdgeneration

Meteosat, which will probably

be operational in 2017. This will allow a

higher resolution and offer more variables,

thereby improving the forecasting quality.

Comparable services

Is Spain an advanced country when it comes to weather services?

I would support that. The quality of our forecasts is essentially

the same as in the rest of the advanced countries of Europe.

And from the point of view of your available resources?

We have what is necessary to become members of various

European consortia. Meteorology has been a global science

since the invention of the telegraph and the first weather

maps were produced from the meteorological data that

were transmitted, with observations being transferred

in this way to forecasting maps. At AEMET we also have

antennas to receive images and data from the US satellites

operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration (NOAA), which means that we do not have any

problems in terms of lack of technical equipment.

It is said that in 2012 there will be problems with solar winds

that will impact on communications. Will they be affected?

There are certain concerns. At the last meeting of the

American Meteorological Association, NOAA put forward a

proposal on the need to do more in-depth work on this. The

subject is not exactly meteorological but about the impact on

satellites and communications.

Worrying for the climate

What is being observed on climate

change?

There are two aspects concerning

climate-change support policies. One

is monitoring, which is not only for

forecasting but is also used for climatology

and for observing changing trends.

Our main task is to take note of what

is happening and to communicate it.

Our other role is related to scenario

modelling. Climate scenarios up to

the year 2100 can be downloaded from

AEMET’s website for each Autonomous

Region, something that has been done

at the request of the sectors involved.

The public feel that climate activity

may have some impact on their lives

and their activities. These models

and the agreed scientific evidence

say that by the end of this century, we

will suffer temperature increases of

between 3 and 5 degrees. Right now, there is no scientific tool better than

climate models. They conclude what

would happen if the rate of emission

of greenhouse gases does not change,

and this is not a prediction but a

projection.

According to environmentalists, if we

do not reduce greenhouse emissions,

climate change may become irreversible.

Once greenhouse gases are released

into the atmosphere, they remain there

for hundreds of years. Some of them

remain for a longer time whereas

others stay for less. Any solutions

adopted now will be felt within 30 or

40 years. We do not have scientific

evidence that might lead us to think

that this is not being caused by human

action; in fact, if we try to explain how

the climate has developed in recent

decades with our best models, the change is not adequately reflected,

and we only succeed if we simulate the

effect of greenhouse gases increase.

It is therefore irresponsible to ignore

this, which means that we must try

to reduce emissions. But the problem

is quite complex. It requires political

decisions affecting development and

life quality, which must be adopted

by all countries, and, as we all know,

there are some countries that are not

willing to do this for the time being.

What is the value of climate forecasting?

Climate projections, and particularly

those of a regional scale, constitute

one of the essential starting points for

assessing impact, vulnerability and

future needs to adapt to climate change.

For AEMET, this is therefore a key priority

in its objective of providing the most

effective weather and climate information

for citizens. The first regionalised

projections of climate change were

presented by the Agency in 2007 and the

information generated was immediately

uploaded on to the Website and made

available to users. In July 2010 the

second phase of updating these regionalised

scenarios was carried out

using new data from the global models.

It resulted in the basis of the Fourth

Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change

(IPCC), approved in Valencia in 2007.

And when this interview is published,

the Agency will already have more

detailed results from various statistical

dynamic models available and freely

accessible on its website. All this

demonstrates the Agency’s desire

to always offer the best available

information on the probable development

of the climate in Spain.

Normal values

In climatology, the normal value of a climatic factor is the average value over a period of time that is long enough to allow short-term fluctuations, i.e. such as interannual variation. In order for climate data to be compatible and comparable in the various regions of the planet, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has defined a time interval of 30 consecutive years to calculate these normal climatological values, this period being known as the “reference period”.

Source: AEMET “Note on the average variation in temperature and precipitation in Spain between the 1971-2000 and 1981- 2010 reference periods”.

For more information, please look up:

- AEMET

www.aemet.es - ECMWF: European Centre for Medium-Range

Weather Forecasts

www.ecmwf.int - WMO: World Meteorological Organization

www.wmo.int - EUMETSAT

www.eumetsat.int - NOAA

www.noaa.gov - IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

www.ipcc.ch

© AEMET

© AEMET

AEMET Headquarters

AEMET Headquarters

Ricardo García at the AEMET forecasting room

Ricardo García at the AEMET forecasting room

Electric storm at Barcelona. Spain

Electric storm at Barcelona. Spain

Cynthia storm image captured by Meteosat-9 (27th February 2010)

© 2010 EUMETSAT

Cynthia storm image captured by Meteosat-9 (27th February 2010)

© 2010 EUMETSAT

© AEMET

© AEMET