You are in:

- Start

- Interviews

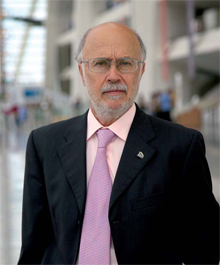

- Manuel Toharia: Science Director of City of Arts and Sciences and Director of the Prince Felipe Museum of Science. Valencia - Spain

Manuel Toharia: Science Director of City of Arts and Sciences and Director of the Prince Felipe Museum of Science. Valencia - SpainNATURAL PERILS

Born in Madrid on 3 August, 1944, he studied at the French Lycée in Madrid where he gained both French and Spanish qualifications (baccalauréat Mathématiques Élémentaires, and completion of a pre-university science course). He went on to study Physical Sciences at the Universidad Complutense of Madrid, specialising in Astrophysics and Cosmology. From 1969 to 1975 he worked as a career civil servant for the National Weather Service (Spanish Air Ministry).

As a professional communicator, since 1970 his activities have focused on journalism and popular science in the press, on radio, on television and in interactive museums. From 1970 to 1979 he was the science editor of the Madrid daily, Informaciones. From 1980 he directed and presented various cultural and scientific programmes for Televisión Española (Spanish TV), where he had worked as a science writer and weatherman since 1971. He was also a science writer for the Spanish newspaper El País from 1980-1981. He was involved in the launch of the Muy Interesante magazine in 1981, and in 1983 he established the scientific journal Conocer, which he ran until 1988.

Since then, he has worked on the production of popular science videos and television programmes and on the conceptual design of exhibitions and interactive museums devoted to science, technology and the environment. Since 1980 he has also had frequent spots on various radio stations, talking about topical scientific subjects, and he regularly collaborates with newspapers and magazines. He is a regular lecturer throughout Spain, giving around a hundred talks each year. He also teaches science journalism on the Master’s course in journalism at the Universidad Autónoma of Madrid (UAM-El País School of Journalism) and at the Spanish Energy Institute. He has been the Director of the ACCIONA Interactive Science Museum (1995-1996) in Madrid, and of the “La Caixa” Foundation’s Science Museum at Alcobendas (Madrid) (1997-1999). From September 1999 he was Director of the Prince Felipe Science Museum in Valencia, and is currently the Science Director of Valencia’s “City of Arts and Sciences”.

He is a member of the Spanish Association of Scientific Communication (and the Spanish representative at the European Union of Science Journalists’ Associations, EUSJA), a member of the Board of Directors of ECSITE (the European Network of Science Centres and Museums), Honorary President of the Saint-Exupéry Franco-Spanish Cultural Association, founding member of the Spanish Energy Club, the Spanish Waste Club, the Madrid Mycological Society and the Spanish Meteorological Association, founding member of the Spanish Academy of Television Sciences and Arts, and holds an Honorary Master’s Degree from the School of Computer Science.

He has written 32 books popularising science, the latest being Meteorología popular [Popular meteorology] (1988, Editorial El Observatorio), El libro de las setas [The book of mushrooms] (1989, Alianza), Tiempo y clima [Weather and climate] (1990, Salvat), El clima [The climate] (1993, Orbis), El desierto invade España [The desert is invading Spain] (1994, Instituto de Estudios Económicos), Astrología: ¿ciencia o creencia? [Astrology: science or belief?] (1995), and Micromegas: del dinosaurio amaestrado al agujero de ozono [Micromegas: from the trained dinosaur to the hole in the ozone layer] (1996), both published by McGraw- Hill, Medio ambiente, alerta verde [Environment, green alert] (1997, Acento Editorial, co-authored by Francisco Tapia), El colesterol [Cholesterol] (1998, Acento Editorial), El futuro que viene [The future that’s coming] (1999) and Hijos de las estrellas [Children of the stars] (2000), both in Temas de Hoy, and recently El clima, calentamiento global y futuro del planeta [The climate, global warming and the future of the planet], published by Editorial Debate (2006, Random House Mondadori), El mito de la inmortalidad [The myth of immortality], co-authored by Bernat Soria, published by Editorial Espejo de Tinta (2007), and Confieso que he comido (mis memorias metabólicas), [I confess that I have eaten (my metabolic memories)] published by Editorial Le pourquoi pas (2008).

He has been awarded the Science Journalism Prize by the Spanish Council for Scientific Research (CSIC), the Prize for Popular Science Videos by Casa de las Ciencias (House of Sciences) in La Coruña, the SIMO Prize for Popular Science on Television, the Energy Saving Promotion Prize (Ministry of Industry), the Medal of Honour for Promoting Invention (García Cabrerizo Foundation) and the 2004 Prisma Prize for a life-long career popularising science, by the La Coruña City Council.

“Science is nothing more than the product of human curiosity”” “It is difficult to summarise 41 years of professional life. My persistent dedication to communication has been the key theme, focused almost always on the fields of Science, Technology and the Environment. Doubtlessly, my previous scientific training was a help to me here, at least at the beginning...”

Was it tenacity or luck that enabled a physicist

to become a television weather forecaster, as

well as the best known and most recognized

man of the day?

Meteorology is the physics of the air, so moving

into that field was a logical consequence −just

one more option at a time when I was looking

for work. And explaining the weather on television

called for communication skills, at least

back then− I began in 1969; in my case, those

skills were probably inborn.

How did you make the leap into journalism,

leading to your role as a popularizer of

science?

It was a more or less inevitable progression.

At the same time as my television work, while

I was still a meteorologist with the Air Ministry,

I started to work for “Diario Informaciones

de Madrid”, on a new type of supplement about

science and technology, so I was dealing with

subjects related to meteorology and general

science every day. My daily contacts with television

and the press (and very soon with radio

as well) gave me an inside knowledge of journalism,

as a good “apprentice” for many years.

Many other stages in my career were to follow: I

directed programs for TVE (Spanish Television);

I was the science editor for “El País”, a daily

newspaper; I founded and created “CONOCER”

magazine; I produced video and TV programs

on science; I was a scriptwriter for interactive

exhibitions, and director of several museums...

From 1976 onwards, I took extended leave from

meteorology, and I have never returned to it. I

can look back on 41 years of continuous involvement

in these areas, not to mention the 36

books that I have written on these subjects.

If we go beyond academic definitions, how

would you describe science? Does it always

have to be viewed from a dynamic perspective?

Science is nothing more than the product of

human curiosity, which makes us constantly

ask ourselves why −and how− it is that things

are as they are, how they work, and what advantages

can be had from a better knowledge

of everything that surrounds us... Animals and

plants do not ask questions themselves; they

simply do what their genetic message tells

them to, in a predetermined way and with very

few variations. Thanks to curiosity, human

beings have developed a culture that is both

instrumental −technology− and intellectual −

science and art; it has given us some amazing

advantages over our environment, even including

remarkable ways of extending our life

span, which was not very long to start with.

Science is nothing more than the product of human curiosity, which makes us constantly ask ourselves why −and how− it is that things are as they are, how they work, and what advantages can be had from a better knowledge of everything that surrounds us

Why has Spain shunned its scientists, or at

least failed to encourage them?

This has not always been the case, although

the mystic, artistic and literary spirit has generally

been far more predominant in this country

than pragmatic, scientific and technical thinking.

This is the opposite of what happens in

other countries, especially the Anglo-Saxon

countries in more recent times. Several centuries

ago, we did not know how to take advantage

of the Toledo School of Translators and the

heritage bestowed upon us by the rich culture

of the Arabs. After that, to some extent, we

missed out on the technological revolution that

started with the steam engine in England and

continued in other countries. And then, in the

twentieth century, apart from the two World

Wars, our own Civil War did not do much to

help the development of science in Spain… Maybe we missed a marvelous opportunity in

the nineteenth century, when science began

to flourish in an exciting way − in Valencia for

instance, where Santiago Ramón y Cajal launched

out on his brilliant career, and in other

major universities too. But then, the twentieth

century stifled virtually all of this impetus: the

best scientists started their careers here, but

went on to achieve prominence elsewhere.

That applies not only to “our” 1959 Nobel laureate

Severo Ochoa, but also to many others

who may not have won a Nobel prize, but who

took the best of Spanish science to other countries,

mainly the United States.

The mystic, artistic and literary spirit has generally been far more predominant in this country than pragmatic, scientific and technical thinking

In spite of its shortcomings, science in Spain

is enjoying something of a heyday at present,

due to the huge influence of North America’s

scientific leadership and the initiatives under

way in Europe. But what must we still do to make advances in every respect, quantitative

as well as qualitative?

It is becoming more and more difficult to talk

about “Spanish” science, or “French” science,

or indeed science in any single country. In an

extraordinary way, science has become international

over the last few decades. The major

achievements and the most outstanding publications

rarely −in fact, never− originate from

one individual, but from many. Up to a hundred

scientists from numerous countries were involved

in publishing the sequences for certain

human genes, and each of them contributed

something to this work. Is the work that many

Spanish scientists are doing in the USA (or elsewhere)

Spanish science, or American science?

The financial and material resources come

from America, of course, but what the scientists

learn and what they perhaps bring back with

them when they return (if they return), and what they basically contribute to human knowledge −

all of that is universal. Not just American… For

scientists who were born and educated in Spain,

the advances that they make on foreign soil

entail better contact with the international research

environment. And better integration into

the productive environment, that is to say essentially,

the world of private entrepreneurship;

something that is far from desirable in Spain.

It is no bad thing for us to export our best brains, even if they do not return later on; what we are really doing is to educate good scientists and technologists so that other countries can reap the benefits

Budgets allocated to scientific programs and to

research, development and innovation have been

described as inadequate. The lack of opportunities

for young researchers is prompting the

large-scale export of brainpower that Spain is

experiencing. How can this situation be changed?

When you use the word “inadequate”, some explanation

is called for, because science does not

need to depend solely on public-sector budgets

and R+D policies. Private enterprise in Spain has

been, and generally still is, very reluctant to undertake

research (or applied research) on its own behalf,

or in cooperation with public scientific institutions.

After all, our figures for public investment

in this field are lower than those of the countries

we would like to resemble, and when it comes to

private research, they are actually far lower. On

the other hand, it is no bad thing for us to export

our best brains, even if they do not return later on;

what we are really doing is to educate good scientists

and technologists so that other countries

can reap the benefits. In terms of the progress of

science as such, it does not make much difference;

but when we start talking about the economic aspects,

we are clearly confronted with a bad deal.

Changing the situation is not easy; maybe Spain

trains more high-level scientists that its scientific,

technological and entrepreneurial structure can

absorb. And this inevitably leads to the exodus of

brainpower − even more so in a world where international

exchanges between such experts are

increasingly encouraged.

It is a curious phenomenon that the longer we live, and the better we live, the fewer risks we are prepared to accept

What role do scientists have in society, and

who is responsible for popularizing science

and scientific issues?

Scientists are the foot-soldiers of a worldwide

human mission that, throughout history, has

enabled us to attain ever higher levels of wellbeing

and longevity. That is their role; it is neverending,

and it becomes more difficult to comprehend

as time goes on; and it is a role that the

rest of the human race does not understand very

well. This is what makes popularization so vastly

important; the aim must be to build some bridges

– building all of them would be an impossible

task– between what science knows, and what society

knows. Making science popular is no easy

matter; in some ways, it is a sort of journalistic

assignment, rather like that of a correspondent

sent to a foreign country which in this case is

the realm of science. To achieve this, it is necessary

to have an adequate understanding of both

worlds: the world of the street, and the world of

the researchers. Popularization is a sort of ongoing

informal education for every citizen, and it has to be financed by the public authorities in

the same way as formal or controlled education.

Also, it must be undertaken by those who know

how to do it well, regardless of whether they were

originally scientists, journalists or teachers.

As risk is an inevitable element of progress, insurance aims to offer a way to redistribute risk and compensate losses

It is clear to me that a large section of the general

public is highly interested in scientific

developments and research results, which

form the basis for our present and future wellbeing.

Does society’s support for its scientists

lead to higher financial contributions?

What you say about support from a good proportion

of the population is definitely true, at

least if you trust the answers that the Spanish

give in surveys. But I very much doubt whether

these answers reflect the deeper thinking of

people who respond in this way. They answer

like this “to make a good impression” – just as

happened with the documentaries shown on

the TVE 2 television channel, which were the

most interesting programs in the entire schedule,

but nobody watched them. This support

always becomes much more qualified when it

is converted into money. And that is why, at the

end of the day, it is not unusual for the politicians

to allocate low funding to science.

How do you perceive risks? In terms of popularizing

science, what could be done about

risks and their consequences? What is your

view of insurance?

It is a curious phenomenon that the longer we

live, and the better we live, the fewer risks we

are prepared to accept. We become more and

more afraid that bad things could befall us, to

the point where we even invent them for ourselves.

However, it is obvious that there is no

such thing as an activity that entails zero risk;

the ecologists have sometimes propounded

this myth, for example by demanding that certain

industrial activities should not present any

risk at all. So, knowing that risk is an inevitable

and also necessary element of progress, it

seems obvious that we should be ready to do

everything we can to minimize it and, on the

other hand, that we should try to compensate

for damage or losses if they occur –which is

always possible– by means of some sort of

system that redistributes risk and provides

compensation. Such as the insurance sector,

for example, not only in the context of science

and the advances that it achieves, but also at

all other levels of everyday life.

Valencia’s City of the Arts and Sciences is a project

that is unique in the world, and it certainly is the

first of its kind. Some questions about the particular

museum that you direct: How was it conceived?

What was its mission? How will it develop in

the future? And what legacy does it hope to leave?

The philosophy of the City of the Arts and Sciences

is enshrined in its own name: one single

culture that integrates the sciences and the arts.

Starting from there, each element safeguards

one aspect of this integral culture that we aim

to preserve: opera, ballet and chamber music in

the Palace of the Arts, the interactive popularization

of science and the debate about Science,

Technology and the Environment in the Museum

of Science; the popularization of natural (mainly

aquatic) science at the Oceanographic Park; popularization

of the arts, documentary material,

exploration and innovation in the audiovisual

sphere at the Hemispheric Theater; and the integration

of modern sculpture into the greened

urban environment in the Umbracle Park. All of

these elements are accommodated in impressive

architectural settings and structures that are

the work of Calatrava, the Valencian architect – he

truly is a prophet in his own country. The content is

continuously renewed, with the result that about

five million people visit the complex each year. I

do not aspire to leave any particular legacy; as the

scientific director of the complex, and formerly

as director of the museum, my idea has always

been the same: to convey interesting and curious

aspects of the world of culture to the general public,

with the aim of helping them to have a better

understanding of the world in which they live, to

enjoy more of its many benefits, and to find more

efficient ways of resolving the equally numerous

difficulties that it presents.

www.cac.es

Mr. Manuel Toharia’s observation

I would just like to recall that there would be less bamboozling if there were not so many unwitting victims ready to be bamboozled. And the way to reduce the number of unwitting victims is simply to provide a little more integrated culture for the general public - culture that must be favoured and fostered by the public authorities as well as by private initiatives. We shall all emerge as winners if we fight this battle in the right way.

The Hemisféric building in Valencia’s City of Arts and Sciences

The Hemisféric building in Valencia’s City of Arts and Sciences© Matej Kastelic / Shutterstock.com

Closing paper of MAPFRE International Conference on Natural Disasters, October 2008 © Alberto Carrasco

Closing paper of MAPFRE International Conference on Natural Disasters, October 2008 © Alberto Carrasco

General view of the City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia

General view of the City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia